Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

A confession: although I come here to sing the praises of little-known horror writer Ken Greenhall, I myself know nearly nothing about him! He was born in Detroit in 1928 and in the 1970s and ’80s wrote a handful of paperback horror novels under his own name and the pseudonym Jessica Hamilton (I was able to learn that was his mother’s birth name). No interviews or photos are online, and only the scantest biographical info is available.

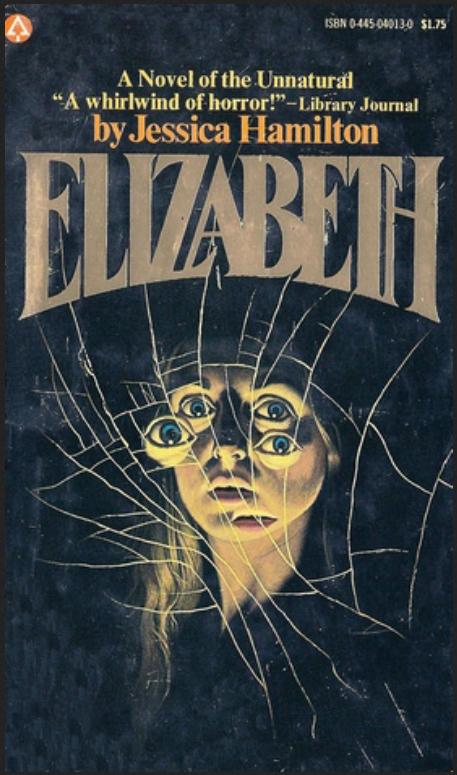

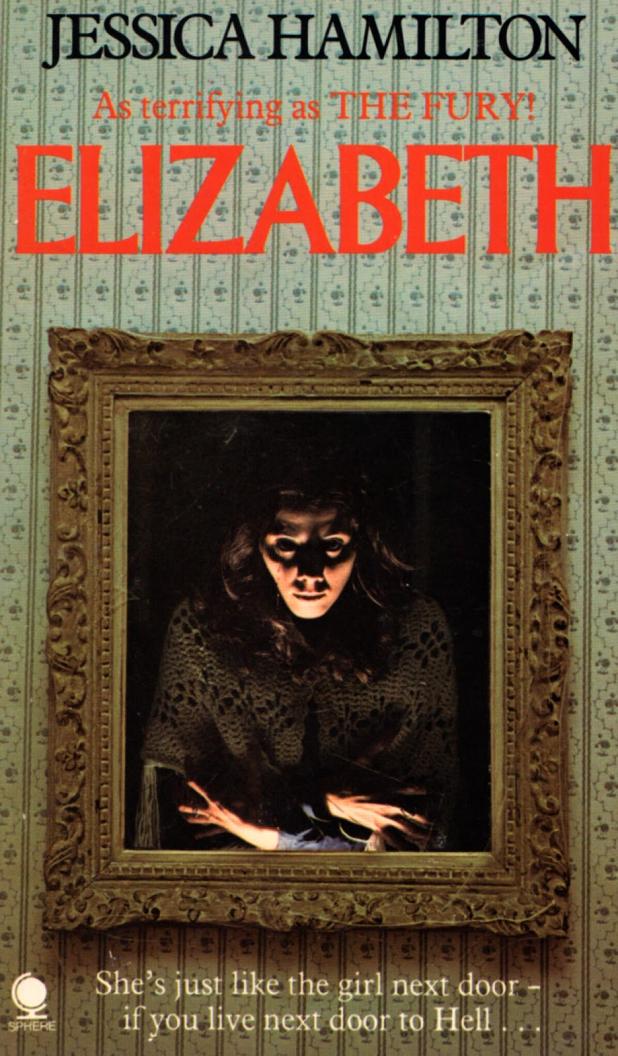

Shame, because would I love to know more about the guy who penned two obscure yet virtual masterpieces of vintage horror fiction: Elizabeth, written under the Hamilton pseudonym, published in 1976, and Hell Hound, by his own name, from 1977.

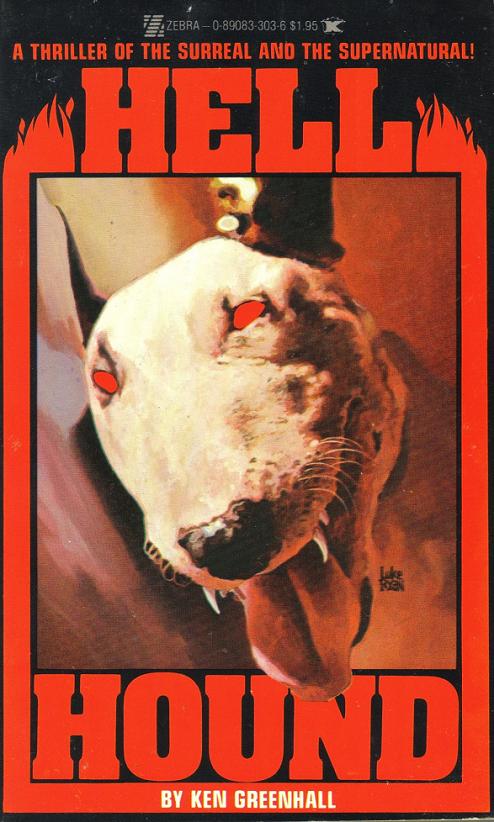

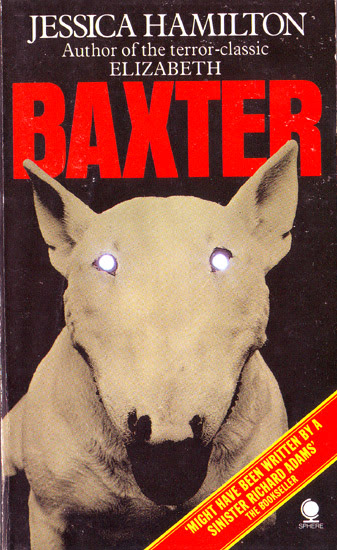

By appearances, Hell Hound (Zebra Books, Oct 1977) seems to be a cheap, tawdry knockoff thriller, just another nature-gone-amok horror novel in the wake of Jaws, except this one is exploiting an animal near and dear to the human heart. The name Ken Greenhall is familiar to no one, there are no blurbs from famous authors or reviewers, and those eyes, those demonically crimson canine eyes, oh man, that is just the cheesiest, just the worst, seemingly stuck in lazily as the cover went to print. So you can’t be blamed for thinking Hell Hound is bottom-of-the-barrel Zebra garbage. You’d be wrong though. Hell Hound is a revelation: dog as sociopath (that tagline “A thriller of the surreal and the supernatural” is just an irrelevant Zebra add-on). In fewer than 200 pages, we are privy to the mind of man’s so-called best friend. Baxter makes Cujo seem like a clumsy and witless amateur.

Greenhall tells this story with the utmost conviction, and that’s why you won’t be able to put Hell Hound down, even though you’ll want it to last and last. What is it about Greenhall’s style that I find irresistible? What makes it feel so authentic, so true? Beneath the cadence of Baxter the bull terrier’s thoughts there is the insistent rhythm of madness—the madness of pure unfettered rationality, unencumbered by the human emotional palette. His narrative voice is detached but brilliant, its psychological insights deft and razor-sharp, its originality startling. This dog regards humans with an almost contemptuous wonder:

Pity is not something I want to encourage in myself. It is something for humans to feel, one of the jumble of odd sentiments they burden themselves with. Their emotions are like diseases, I think; diseases that can spread among those who try to understand them. Let their feelings be a mystery, like the dozens of other strange traits they have… The ways in which they deceive themselves are endless.

Baxter’s interior monologues gird the novel; every eight or 10 or 12 pages we have one or two pages of his italicized ruminations on the inscrutability of humans and how his life interacts with theirs, among other things. One of my favorite things about Hell Hound is how the worst scenarios play out: there are no surprises, only a sense of fate predetermined. In a way the story is tragedy, the seeds sown within our very natures, beast and man alike. So when we meet Baxter, he is lamenting his life with uninteresting and unbearable owner, the old, joyless, widowed Mrs. Prescott, and showing a keen interest in the young, vibrant, erotically-charged couple moving in across the street, and wondering:

What are the possibilities of my strength? That is a thought I have never had before. What if some morning as the old woman stood at the head of the staircase, she were suddenly to feel a weight thrusting at the back of her legs?

The dispassion in Baxter’s voice is electrifying. Life in Mrs. Prescott’s perhaps lower middle-class home is a dreary affair. A widow whose daughter’s husband breeds dogs, of which Baxter is one and given to her after her husbands dies, Prescott is distrustful and uptight, withholding of affection, and feels neither one way or the other about the bull terrier: “She had never been able to decipher his expressions. He had always looked either impassive or malevolent to her.”

Baxter is intrigued by his own conflicting feelings about her; the first time he nudges her at the head of the staircase he pulls her back in time using his powerful jaws. He tries to escape to the couple across the street—“I need their joy”—but of course he is brought right back. Baxter has no choice, and her death seems foretold for her: “She had given her affection to another creature: an act she had all her life been convinced was dangerous. Now she knew she had not been wrong to mistrust affection…” and as her head hits the floor at the bottom of the stairs: “There was a faint aroma of floor polish. She smiled. ‘I was not wrong,’ she whispered.”

The plan works: Baxter is taken in by the Graftons across the street, after Florence, Mrs. Prescott’s bitter, alcoholic daughter with repressed lesbian tendencies (many a character is repressed, a failure, or a fool), offers them the creature. Greenhall’s economic, precision-point insight into even the human psyche cuts deep and true, as Florence regards the upwardly-mobile John and Nancy as something probably like liberal do-gooders (there is a mildly discernible undercurrent of class satire throughout the novel). Those familiar bitter disappointments that rise from our lives and poison us:

Take the beast, she thought, take the people, the houses, the trees. Have as many pregnancies and ideals as you can manage; you won’t save any of it. Something or someone will defeat you.

Once ensconced in the Grafton home, Baxter feels satisfaction and control, and knows the man and woman rely on him. There is order, a place for everyone. This is how he was meant to live, this is the natural way of things between an animal and its humans.

My pleasure increases endlessly… She has learned to feed me fresh, raw meat. She brings me large, mysterious bones, which I crack fiercely, feeling pride and pleasure in the strength of my teeth and jaws.

And then the inevitable for these newlyweds, which bodes unwell for our boy Baxter. Ever observant, he realizes “the woman is changing. Her body is becoming thicker and thicker, and there is an added scent about her that I find unpleasant. It is almost as if she had the scent of two people.” Ruh-roh. And it all plays out precisely as you think, which makes it all the scarier. The newborn’s mindlessness and many stupidities offend Baxter’s notions of power and weakness, and he resents the parents’ dotage on the offspring, and he now waits for an opportunity to—well, you know. And after Baxter realizes too late, their love has turned to insurmountable fear.

Baxter is next given to yet another neighbor family. The son is Carl Fine, a 13-year-old loner who spends time in a bunker-like hideaway he’s built in the junkyard. Carl is fond of—wait for it!—Hitler, as well as Eva Braun, their dogs, and their final days in a bunker of their own. His idea of flirting with a neighbor girl, Veronica Bartnik, who shows interest in him is to tell her about ol’ Adolf and his dog Blondie:

“He had these cyanide capsules he was going to use to kill himself and Eva. But he wasn’t sure they would work – he didn’t rust the people that gave them to him. So he gave one to Blondie. He watched her die. Then he had her puppies shot.”

What a charmer! It’s no surprise Baxter and Carl hit it off, and their relationship is a push and pull of authority and understanding. Baxter mates with Veronica’s father’s hunting spaniel; Carl starts staging junkyard dogfights with Baxter; and finally, Carl and Veronica’s friendship turns physical. When Carl tries to sic Baxter on a 10-year-old boy—which Baxter refuses to do—Baxter sees treachery, a corrosion of their relationship, and wonders if “the day will come when the respect will no longer be there. I wonder whether he could ever be so foolish.” That day will come, have no doubt, spurred by the malicious murder of Baxter’s offspring and Carl’s own growing sociopathy.

This is horror found in one of our most recognized and beloved animals, one with which countless millions have bonded daily for millennia, one which seems to exist in our world but is more like an utter alien, staying its power till that moment in which we innocently bare our hairless throats to its ivoried jaws, and then revealing what its forgotten instinct has been since birth.

You’ve met Baxter, now allow me to introduce Greenhall’s other great character of dreadful ruthlessness. At just 14 years old, Elizabeth Cuttner is a startling little sociopath with powers natural and not. In Elizabeth, she tells her story in a voice quite distinctive, yes, but also as cool and unforgiving as a marble tombstone. With dispassionate precision, she grasps the motivations of those around her, fathoms their subconscious desires; Elizabeth has psychological insights that people thrice her age never attain. She amazes, charms, bewilders, and ultimately horrifies. She tells us on the very first page:

You’ve met Baxter, now allow me to introduce Greenhall’s other great character of dreadful ruthlessness. At just 14 years old, Elizabeth Cuttner is a startling little sociopath with powers natural and not. In Elizabeth, she tells her story in a voice quite distinctive, yes, but also as cool and unforgiving as a marble tombstone. With dispassionate precision, she grasps the motivations of those around her, fathoms their subconscious desires; Elizabeth has psychological insights that people thrice her age never attain. She amazes, charms, bewilders, and ultimately horrifies. She tells us on the very first page:

When I was younger I saw James, my father’s brother, look from our dog to me without changing his expression. I soon taught him to look at me in a way he looked at nothing else.

Elizabeth lives in lower Manhattan, in a very old building not far from the once-bustling harbor. Her grandmother appears each evening in a full black dress and tells ever-changing stories about the family’s ancestry at dinners to the remaining members of the Cuttners: the aforementioned James, her son; his wife Katherine and their son Keith. The live-in servants are the Taylors, who reside in the basement but have little interaction with the family (“I suppose there is no need to speak to those whose dirt and appetites you know intimately”). Grandmother’s husband left her years before, but his office building is next door. Oh, Elizabeth’s parents? You can probably guess why they’re not around, can’t you?

The supernatural slips in very early but oh-so-quietly. In the second chapter, Elizabeth and her parents vacation in a cabin at Lake George, and while on a nature walk she finds an unlikely-looking toad “the color of decaying meat” and takes it home, then she is compelled to hold it between her breasts. As she does this, a visage swims into view in the antique mirror in her room. “Do not fear me, Elizabeth. I have come to help you.” She has a fearsome beauty and speaks in an antique language; her name is Frances, a distant Cuttner relative; indeed, we learn she is an English witch from centuries past. Elizabeth seems to fall in love or obsession with Frances, who wants to reveal and guide all of Elizabeth’s familial powers… and warns Elizabeth of the new tutor from England that James has hired for her, Miss Barton. Young Miss Barton, who strangely resembles the woman in the mirror.

Greenhall is a master of insinuation. There is barely a whisper of actual violence or overt sex, yet the novel seethes with these powers, and the tone throughout is controlled and affectless. Emotional turmoil swirls and eddies beneath that undisturbed surface, whether its origin is otherworldly or not. Affairs that speak more of desperation and opportunity than real human feeling spring up in the home. This subversion of bourgeois homelife feels like hedonistic freedom, an exposure of the hypocrisy necessary to hide and/or deny true human motivations.

Elizabeth is a young woman who accepts impassively the male sexual appetite—especially when it serves her own needs and ends, and is the root of domestic conflict. Her knowledge of male vanity, and flattery of such, is complete. Elizabeth notes that “James feels about the Don Juan legend the same way a priest feels about the New Testament.” Something seems to be going on between Katherine and Miss Barton too, but that’s only par for the course:

James had never been happier. He accused Katherine of being in love with Miss Barton and pretended to be outraged. Actually, the thought of his wife being involved with another woman excited him… he became much more open about his relationship with me and on afternoons when Katherine and Miss Barton were uptown shopping together he would take me to his wife’s bed. “You be Katherine,” he’d say, “and I’ll be Miss Barton.”

Greenhall is in full command of the writing craft, knowing what to tell, what to show, and most especially what to conceal—and ironically in that concealment, revealing all. Whatever she is—witch, “bad seed,” Lolita, possessed—Elizabeth is an amazingly complex and captivating character. Her voice is so confident, so ageless, so wise, as she begins to use her unnatural talents to harm others, such as Grandmother:

“Martha,” I found myself saying, “with my gift and power I bid thee desist. Martha Cuttner, I bid thee vanish. Thrice, Martha Cuttner, my gift and power bid thee desist and vanish.” And then there was silence. Behind me stood the city and its people. Some of those people had passed me on the street and admired me, thinking I had never done unmentionable things in the night, as they had done or wanted to do.

Elizabeth and Hell Hound are two of the most intriguingly written novels I’ve read in 1970s horror, deceptively rich and rewarding, works of literary skill lurking beneath tacky paperback covers. Forgotten by all but the most avid horror fiction fans (and I must thank the Phantom of Pulp blog for turning me on to them several years ago), these two novels get my highest recommendations. If you enjoy the chilly, literate, ironic dark fictions of Shirley Jackson, Peter Straub, Roald Dahl, Patricia Highsmith, J.G. Ballard, or Iain Banks, you will appreciate Greenhall’s singular talent for saying so much by saying so little.

While Elizabeth is widely available as a cheap used paperback, Hell Hound has been an expensive collectible for some time (perhaps because in 1990 it was made into the French thriller film Baxter). I hope one of the several publishers making horror fiction of this era available to contemporary readers will reprint Ken Greenhall’s work; until then, I recommend you keep a close eye on the horror fiction shelves of used bookstores everywhere.

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.